He Feasted Sumptuously Everyday: The Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus

|

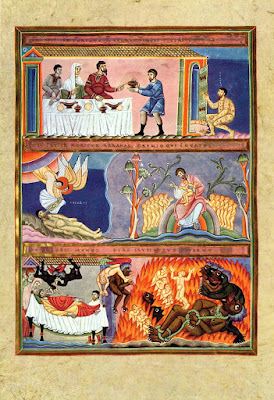

| Lazarus and Dives, illumination from the Codex Aureus of Echternach |

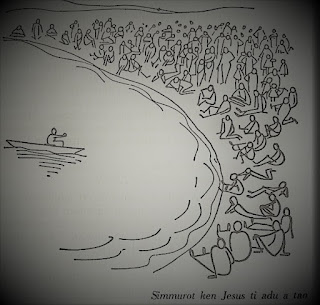

I took a plane to Leyte. That was some years ago. Since there were no newspapers nor in-flight music, part of the entertainment onboard was a game hosted by the flight attendants. A prize was at stake for the first passenger who could produce a picture of a sad person. I don’t think I had one nor the rest of the passengers. Who would ever face a camera sad? But then a guy pulled out his wallet and produced a 500 peso bill with Ninoy’s “sad” face on it.

Who thought that there’s sadness in money? Even the book of Proverbs says “Wealth adds many friends” (16:4).

Luke Chapter 16: Two Parts of the Parable

Luke chapter 16 is famous for being the gospel on wealth. Four times the word “rich” is mentioned and three times for “wealth”. The chapter begins and ends with stories that open with the phrase “there was a rich man” (v. 1 &v. 19).The last part of this chapter, the Gospel reading, narrates the famous Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus (vv. 19-31). We should take notice here of Jesus’ addressees of this parable– the “lovers of money” (Gk. philarguroi v. 14)

The parable can be divided into two parts: the first is the story of the reversal of fortunes of two men (vv. 19-26) and the second is the story of the five brothers (vv. 27-31). This latter part is often missing in many homilies.

Part I: Reversal of Fortune

Luke’s first example of the reversal of fortune is found right at the beginning of his gospel, in the Song of Mary (or Magnificat). The “lyrics” are bold:

“He [God] has brought down the powerful from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly; he has filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich away empty” (1:52-53).

With this, Luke initiates an important theme of his gospel: reversal of fortunes.

To have an idea of what a sumptuous feast is like, we can read from a Roman novel written in the first century A.D. on a dinner hosted by Trimalchio, a member of the Roman nouveau riche. Food is endless. Eat all you can. There’s a set of the dish each representing every sign of the Zodiac which is served course by course by a fleet of servants. Name it and Trimalchio has it, including live birds sewn up inside a pig. Even their names speak of pomposity. His wife’s name is Fortunata and Trimalchio means “thrice-blessed”.

The name of the rich man in Jesus’ parable is known in the Latin translation as Dives (“rich”). But this is missing in most older manuscripts. Perhaps, Luke intends that the rich man is anonymous, an open figure. So any rich person should be a candidate.

“He [God] has brought down the powerful from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly; he has filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich away empty” (1:52-53).

With this, Luke initiates an important theme of his gospel: reversal of fortunes.

The Anonymous Rich Man

In the parable, the rich man’s lifestyle is enviable: “dressed in purple and fine linen” (v. 19a) — signature clothes at that time, only royalties could afford (see Esther 1:6); and “feasted sumptuously every day” (v. 19b).To have an idea of what a sumptuous feast is like, we can read from a Roman novel written in the first century A.D. on a dinner hosted by Trimalchio, a member of the Roman nouveau riche. Food is endless. Eat all you can. There’s a set of the dish each representing every sign of the Zodiac which is served course by course by a fleet of servants. Name it and Trimalchio has it, including live birds sewn up inside a pig. Even their names speak of pomposity. His wife’s name is Fortunata and Trimalchio means “thrice-blessed”.

The name of the rich man in Jesus’ parable is known in the Latin translation as Dives (“rich”). But this is missing in most older manuscripts. Perhaps, Luke intends that the rich man is anonymous, an open figure. So any rich person should be a candidate.

Lazarus, the Poor

The poor man (Gk. ptochos) has a name, “Lazarus” meaning, “My God help”.It sounds like a prayer more than a proper name. Indeed for his situation described in the story, he would need a lot of divine intervention. He is dumped right at the gate of the rich man, probably a cripple. He is covered with sores.

In the book of Job, when the three friends saw that Job was covered with sores, they did not recognize him so they wailed, tore their robes, and threw dust in the air upon their heads. “They sat with him on the ground seven days and seven nights, and no one spoke a word to him, for they saw that his suffering was very great” (2:12-13).

Lazarus was hungry, longing for something from the rich man’s table. The picture is not of Lazarus wanting to fill his empty stomach with crumbs as often portrayed by artists and preachers. Lazarus is at the gate, just a few meters from the scene of feasting. We wonder why the rich man is never aware of the presence of a poor man at his very own gate. Perhaps, the phrase “what fell from rich man’s table” (v. 21) is a metaphor for help that is expected of a rich man. Sharing of possession is a major theme in this chapter (see The Parable of the Dishonest Manager in Luke 16:1-13).

In any case, no help comes to Lazarus but dogs that come to lick his sores. The dog is man’s best friend, indeed.

When the rich man died, he is buried, period. No eulogies as is commonly given to a dead rich man. The parable says he is in Hades, the place of the dead in Greek mythology (Homer).

Lazarus was hungry, longing for something from the rich man’s table. The picture is not of Lazarus wanting to fill his empty stomach with crumbs as often portrayed by artists and preachers. Lazarus is at the gate, just a few meters from the scene of feasting. We wonder why the rich man is never aware of the presence of a poor man at his very own gate. Perhaps, the phrase “what fell from rich man’s table” (v. 21) is a metaphor for help that is expected of a rich man. Sharing of possession is a major theme in this chapter (see The Parable of the Dishonest Manager in Luke 16:1-13).

In any case, no help comes to Lazarus but dogs that come to lick his sores. The dog is man’s best friend, indeed.

Reversal of Fortune

Finally, both of them died. Here begins the reversal of fortunes. Lazarus is “carried away by the angels to be with Abraham.” Very often, in the Old Testament, the reward of a righteous life is to be buried with one’s ancestors. That’s why death is described as “being gathered to one’s ancestors” (See Gen 49:33; Num 27:13).When the rich man died, he is buried, period. No eulogies as is commonly given to a dead rich man. The parable says he is in Hades, the place of the dead in Greek mythology (Homer).

And he is being tormented (Gk. hyparchon, v. 23).

Now the rich man looks up and sees Abraham and Lazarus from a distance.

The irony continues. He now notices the poor man though far away while when he was alive he never bothered to see the poor man at his own gate. He calls out for Abraham for mercy while he himself was merciless.

Notice that the rich man still thinks he is still the boss. He’s got no nerve to command Lazarus to come to his aid or to be a messenger.

Notice that the rich man still thinks he is still the boss. He’s got no nerve to command Lazarus to come to his aid or to be a messenger.

Abraham, however, shows him the real status now. He had received “good things during his life” (Gk. ta agatha) while Lazarus received only bad things (Gk. ta kaka).

“But now here” (nun de oude, strong contrast in Greek), he is being comforted while the rich man is “in agony” (v. 25).

As there was a wide economic gap between the rich man and poor man, so there is NOW a great eschatological divide between the two.

Part II: The Fate of Five Brothers

The second part is short, eleven verses only, and almost like an appendix to the story. But then this part is the essential part of the parable.It begins with a short prayer of the rich man (now turned “poor” man) address to Abraham, practically to raise back to life Lazarus (cf. the raising of another Lazarus in John 11:43). He wants him to warn his five brothers. Readers of Luke assume these five brothers are also rich, “dressed in purple and fine linen” and “feast sumptuously everyday.”

But then there is no need for any resurrection, “They have Moses and the Prophets." Jesus refers to the Old Testament (Pentateuch and the Prophets).

Social Justice (Mishpat)

With it, we see that Old Testament is seen as restoring justice for the poor (the Hebrew concept of mishpat). In fact, the prophets' major mission is one of restoring and preserving mishpat. Note that Moses is the greatest prophet (see Deuteronomy 34:10).

The eighth-century B.C. prophets: Amos, Hosea, Isaiah, and Micah are known for their strong indictment against their leaders. Establishing mishpat is the primary responsibility of a ruler.

[You can click here for my YouTube lectures on these prophets].

Thus, the prophet Amos, for example, condemns the wealthy ruling elite of Samaria for their luxurious lifestyle at the expense of the poor (6:4-7):

Alas for those who lie on beds of ivory,

and lounge on their couches,

and eat lambs from the flock,

and calves from the stall;

who sing idle songs to the sound of the harp,

and like David improvise on instruments of music;

who drink wine from bowls,

and anoint themselves with the finest oils,

but are not grieved over the ruin of Joseph!

Therefore they shall now be the first to go into exile,

and the revelry of the loungers shall pass away.

In this text, Amos lists four activities of luxurious living: eating, singing, drinking, and perfuming oneself. In the meantime, these people ignore the suffering of the “ruin of Joseph” (v. 6b). Amos alludes here to the destruction of a certain territory perhaps because of a natural disaster. The point is the insensitivity on the part of the rich - enjoying while many others are suffering.

Eschathology and the Sharing of Possessions

Remember what Karl Marx taught -- “religion is he opium of the masses”? That heaven anesthetizes any striving to make life better here on earth, for the poor simply have to wait for that eschatological reversal of fortunes? He was mistaken.

Just read the prophets; or listen to the prophets (Luke 16:29).

The hope to be in the bosom of Abraham is not a utopia that deadens once senses to the plight of oppressed and victims of injustice. That it is okay for the poor to be poor now, but rich in heaven later. By no means that was the intention of the evangelist Luke.

The eschatological reversal of fortune is addressed to the rich, as we gleaned from the parable. It serves as a strong metaphorical warning for the rich: to start to live a simple lifestyle, share their possessions with the poor, and act in favor of mishpat.

Eschatology has an ethical dimension, as we say in theology.

Resources:

For a synthetic study of wealth and poverty in Luke-Acts, see Carlito C. Reyes, “The Poor and the Rich in Luke,” in Led by the Spirit: Festschrift in Honor of Herbert Schneider, SJ on the Occasion of his 65th Birthday, ed. M. L. Locker (Manila: LST, 2002), pp. 141-153.

For a survey of poverty in the bible, see Leslie J. Hoppe, There Shall Be No Longer Poor Among You: Poverty in the Bible (Nashville: Abingdon, 2004), see esp. 69-72 (on Amos), and pp. 150-156 (on Luke).

Comments

Post a Comment