The Book of Tobit

|

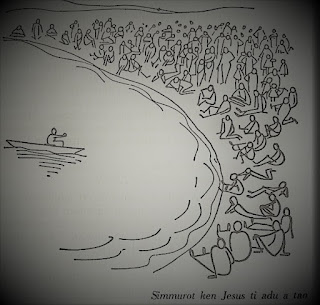

| Wall Painting on Tobit at the Chapel of the Abra Clergy House Magsingal, Ilocos Sur |

The Book of Tobit is not so familiar to us, even if it is supposed to be a "Catholic" book in the sense that it is one of the Deuterocanonicals. Here's an introduction to that book published in the CBAP Old Testament Primer. The author is Fr. Francis Macatangay, one of the Filipino experts in the Book of Tobit. You may want also to read an article I've written on Old Testament initiation stories. Please click here.

Synopsis

The Book of Tobit is one of the seven deuterocanonical books in the Roman Catholic canon of scripture. It narrates the intertwined stories of two pious families of Tobit and Raguel. While living in exile, they experience great misfortunes. Tobit, known for his strict observance of the law and for his deeds of mercy, becomes blind and poor while Raguel’s daughter Sarah remains without a husband despite her innocence and seven attempts at a wedding. The jealous demon Asmodeus kills all of Sarah’s seven previous husbands. In despair, both Tobit and Sarah pray to God, asking the Most High to deliver them from their sorrow and distress. God responds to their prayer by sending his angel Raphael to loosen the white scales that cover Tobit’s eyes and to unbind Sarah from the stronghold of the demon.

To resolve Tobit’s poverty, the story sends Tobiah on a journey with Raphael disguised as a kin companion named Hananiah in order to retrieve a sum of money deposited with a cousin. The journey and the eventual encounter with a giant fish lead to Tobiah’s marriage to Sarah and to the restoration of Tobit’s sight. The story reaches its denouement with the revelation of Raphael as the angel of God who has guided the events behind the scenes. This leads to Tobit’s praise of God and hopes for the future ingathering of scattered Israel in the land. Upon his death, his son Tobiah honors his father Tobit by giving him a splendid and honorable burial.

The Textual Tradition

The Book of Tobit has a complex textual tradition. The story is preserved in its entirety in Greek, with short and long textual forms. The long Greek version is found in codex Sinaiticus while the short version, typically viewed as an abridgment of the long one, survives primarily in the Alexandrinus and the Vaticanus codices. Fragments of Tobit in Hebrew and Aramaic (4Q196–4Q200) have been found at the caves of Qumran. For many scholars, the long Greek version enjoys textual priority because of its textual proximity to the Qumranic fragments of Tobit. Many also believe that the original language of Tobit is Semitic, most likely Aramaic. The translation of Tobit into Hebrew, Greek, and Latin attests to its wide and popular appeal.

The Author and Genre

The author of the Book of Tobit is an unknown Jewish writer who may have been from the land of Israel. It was likely composed between 225 – 175 B.C.E. As such, it is considered an important textual witness to the theological ferment in Second Temple Judaism. By setting the story in the remote time of the Assyrian empire during the siege and deportation of the northern kingdom of Israel in the 8th – 7th century, the story aims to address Diaspora Jews or those who were living away from the homeland. Without a temple, the scattered Jews were encouraged to embrace a life of righteousness defined in terms of truth and charity rather than primarily in terms of cultic practices. The emphasis on righteous living and fidelity to God implies that lively hopes of a return to the land are considerably maintained.

1.5 In writing the story, the author of Tobit combines various literary genres such as hymns, psalms, prayers, instruction, adventure, apocalyptic, prophetic, and folktale, to name a few, in order to form a Jewish novella that edifies and delights with humor and irony. Its textual influences are both biblical and non-biblical. Some of the biblical books that help shape the story include Genesis, Exodus, Deuteronomy, Amos, and Proverbs. To illustrate, the narrative preoccupation with the burial of the dead owes to the type of patriarchal piety found in Genesis. Moreover, the portrait of Tobit’s character is shaped according to deuteronomistic ideals (cf. Deut 6:17-18). Non-biblical texts that are considered woven into the narrative include the Story of Ahiqar, Enoch, the Odyssey, and The Tale of the Grateful Dead. Frank Zimmermann correctly asserts that “in the loom of the Tobit tale, the woof comes from the folklore of mankind, and the warp and the pattern, the vitality and the color come from the religious experience of the Jewish people.”

Literary Structure

Guided by the spaces or locales that the story traverses and the leitmotif of “the road” or “the way,” the main narrative of Tobit is said to possess a chiastic structure. The bulk and core of the narrative is a story of a journey in Tob 4–14. It is bracketed by a prologue that consists of a detailed introduction to Tobit’s character and the situation in Tob 1–3 and by an epilogue that narrates the death of Tobit and the other characters in the story in Tob 14:2-15. The core of the story follows this concentric pattern:

A Tobit’s Words of Instruction Tob 4:1-21

B The Journey from Nineveh to Ecbatana Tob 5:1–7:8

C The Wedding in Ecbatana Tob 7:9–10:13

B’ The Journey from Ecbatana to Nineveh Tob 11:1–12:22

A’ Tobit’s Words of Praise Tob 13 – 14:2

In this structure defined by spatial movements, the wedding of Tobiah and Sarah takes center stage. This is a pivotal event in the narrative flow because it points to a new beginning and the possibility of perpetuating the family line, identity, and, of course, life. In a story that is concerned with exile and the eventual decay and death of Israel as a nation, the wedding of Tobiah and Sarah, children of families threatened with extinction, functions as a sign of a future whereby the threat of death is overcome. With this development, Tobit moves from his despair and inability to praise God earlier to his lavish praise of God later, marking his transformation from physical and spiritual blindness to sight.

Theological Themes

Three main theological themes can be discerned in the Book of Tobit. The first is divine providence. All the major characters in the story have theophoric names, which means that they bear the name of God. Tobiah means that God is my good; Raphael means that God heals. Azariah means that the Lord has helped and Hananiah means that the Lord has had mercy. The names of the characters imply that God, though seemingly absent in their experience of exile, is still very much present to his people. Their names literally manifest God and his actions on behalf of his people. Raphael is, of course, the embodiment of God’s providence and care for his elect. In this regard, Tobit’s blindness is not merely physical; it underscores the overwhelming sense of the seeming absence of God’s light in exile. The situation of exile appears as though God has forsaken his people. And yet, as the story shows, God guides the course of events that will eventually deliver his people from such consuming darkness. God’s providence continues to abide with Israel and it will result in the restoration of all the dispersed to the land. As soon as Tobit’s eyes are opened, he is able to praise God and to hope for God’s promises to be fulfilled. Tobit is able to see that God continues to be active in his life and in the life of Israel.

The second is the emphasis on ethics of righteousness, truth, and charity. Tobit is particularly known for his observance of the commandments and fidelity to the Mosaic Law. He instructs his son Tobiah to follow the precepts of the Lord and not to erase his commandments from his heart. This ethic of righteousness, however, is not confined solely to liturgical activities or Temple sacrifices. Religious piety includes acts of charity. To be righteous, to enjoy the right relationship with God, requires the performance of deeds of mercy such as clothing the naked, feeding the hungry, and burying the dead. In Tobit, the relationship with God is not only vertical (cultic) but also horizontal (deeds for others). This means that the hands of the poor in need are as holy as the altar – they are two ways of rendering service to God.

The third is the importance of hope. This arises from the notion that the exile of Israel is a situation and experience of death. Death is in fact very prominent in the narrative. Tobit buries the dead bodies of his fellow co-religionists in exile. He claims that his blindness is like walking among the dead. Exile is indeed a deathly condition that God alone, in His mercy, can heal. God’s healing of Tobit’s blindness points to God’s future action of healing his people’s situation of death. What God has done for Tobit, God will also do for Israel. And so, the events that have led to Tobit’s restoration, which Raphael has asked Tobit to write, inspire renewed hopes that God will raise and restore his people to life in the land.

Tobit in the New Testament

The Golden Rule in Matthew’s Gospel is found in its silver formulation in Tob 4. The image of the treasure of heaven found in the gospels has its first textual witness in Tob 4. Finally, the story of Cornelius and his conversion in Acts 10 alludes to the story of Tobit. In Acts, the allusion to Tob 12 in Acts 10:1-4 seems to imply that acts of charity, a defining trait of Cornelius, allows him to be incorporated into the Christian family as Ahiqar was into the family of Tobit.

Tobit in the Liturgy

The Book of Tobit is read in the liturgy from Monday to Saturday of the 9th Week in Ordinary Time. Most are exposed to the Book of Tobit, however, by way of weddings. Two passages, Tob 7:6-14 and 8:4-8, which both deal with the wedding of Tobiah and Sarah, are included as options for the celebration of the Rite of Matrimony. Finally, Tobit 13 is recited at lauds on Tuesday of the first week and on Friday of the fourth week while passages from Tobit 4 are used as the reading for Morning Prayer on Wednesday of the first week.

Comments

Post a Comment